Dear Bloom: I want to dress up as samurai for my office Halloween contest. Is this cultural appropriation?

Byline: Written by Jessica Regan, Sr. DEI Advisor at Bloom

Dear Bloom,

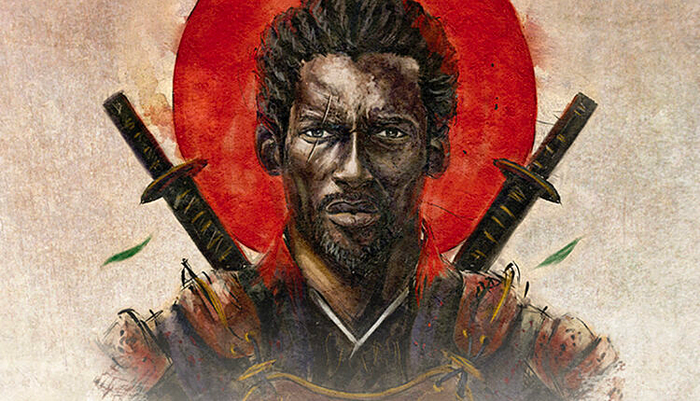

I am a Digital Marketing Director and also a Black man. Our office is hosting a virtual Halloween costume contest this year. I want to dress up as Yasuke, the African samurai (the actual 1500’s Japanese African samurai from the Netflix show). I was introduced to the show Yasuke by my Japanese partner. Upon further research, I found that Yasuke challenges anti-Black attitudes and embodies the sacred core beliefs of samurai culture. I want to represent that.

Being a Black man, I fear my costume could be considered offensive. But like Yasuke, I am a Black man, which adds some nuance worth celebrating. His story is about cultural exchange and acceptance. Something else worth noting, I sit on my organization’s executive leadership team, and I am afraid if I wear this costume, I may be engaging in cultural appropriation. I’m worried this could compromise the DEI efforts our organization has made to be more inclusive. What should I do?

—Hesitant Samurai

Dear Hesitant Samurai,

Firstly, we love a costume contest! As a collective of DEI and HR Advisors at Bloom, we understand why folks might be hesitant to dress up — especially if there are concerns around inclusion. Understanding cultural appropriation can be confusing, especially when we exist in a world that champions cultural pluralism while systemically erasing, co-opting, and exploiting the cultures of historically marginalized communities.

What I find interesting about your question is that it opens up a much deeper discussion on the impact of appropriation at work. Cultural appropriation goes beyond just office celebrations. We observe cultural appropriation in marketing, advertising, company culture, and employer branding. The fine line between cultural appreciation and appropriation is one that historically has been difficult to draw for most organizations. Let’s dig into your question and work to cultivate the tools to identify and avoid cultural appropriation at work (and beyond).

First things first, what is appropriation? Why does it matter?

In the case of your question, Hesitant Samurai, your concern about cultural appropriation isn’t unfounded. Appropriation means using elements of a culture that isn’t your own without an in-depth understanding of the significance and relationship held between the cultural object or practice and the community to which it belongs. Appropriation is the unacknowledged, inappropriate, and non-consensual adoption of the customs, traditions, regalia, objects, hairstyle, or headdresses of one culture by members of another (typically those with more social and political power). Cultural appropriation can also manifest as profiting off of sacred objects, practices, or expressions of self (such as hair, nails, and clothing) while simultaneously not caring about the community it comes from. Like many other Asian cultures, Japanese culture is subject to anti-Asian hate in the forms of racism, xenophobia, the model minority myth, and orientalism. Japanese culture has also been fetishized and hypersexualized. For example, when Gwen Stefani fetishizes the Harajuku Girls or the western world’s obsession with consuming anime while not challenging anti-Asian racist beliefs. Especially in the wake of COVID-19, anti-Asian hate is at an all-time high, and it’s showing up at work too.

It’s important to question the cognitive dissonance that occurs when one wants to consume a culture while existing in a space that still marginalizes that culture.

How cultural appropriation manifests at work

Our culture often places the responsibility of dismantling systems of oppression, like racism and capitalism, on individuals rather than critically examining the broader systems in which we operate. As such, cultural appropriation goes beyond Halloween and offensive costumes. It rears its ugly head when organizations attempt to stay relevant by misusing AAVE in their marketing campaigns (also known as “Digital Blackface”). Or when multi-billion dollar conglomerates like the Kardashians launch products like the Kimono, acting as though they invented this traditional garment. It’s the unchecked exploitation, misrepresentation, behaviours of objectification, and dehumanization of marginalized identities. People often forget that cultural appropriation also includes misrepresenting cultures through messages that reinforce stereotypes and reduce people’s cultures to more palatable versions for mainstream (read: white) consumption. Like Kim Kardashian’s “Kimono,” it removes the intricacies that make specific cultures unique and beautiful.

This is why you can’t appropriate being a “cowboy” or other elements of white culture. Appropriation requires a power imbalance — the (mis)use or adoption of cultural elements from a culture that has been historically subjugated by a more powerful and/or dominant culture. And guess what? Many historians say Black and Indigenous men were actually the first cowboys.

Understanding, honouring, and celebrating the intricacies and nuances of a culture is what sets appreciation aside from appropriation. As such, if one truly understands all elements of the culture in question and understands why those elements are sacred, one is less likely to wear it as a costume or position it as a piece of marketing material.

So, Hesitant Samurai, if you’re still on the fence about your costume (and if you’re worried about putting your organization’s DEI progress at risk), here is a checklist to help you make your decision.

- Purpose: Why are you wearing this costume?

I know the purpose of wearing this costume. [Yes or No]

I’m not wearing this to stay trendy. [Yes or No] - Usage: How are you using this item?

I am not making a joke out of someone’s culture by wearing this costume. [Yes or No]

I am wearing this costume because I love what it represents and not because it's a convenient opportunity to try on something new. [Yes or No] - Significance: What’s the significance of this costume?

I know the history of this costume. [Yes or No]

I know what the costume represents. [Yes or No]

This costume doesn’t represent anything sacred. [Yes or No] - Source: Where did you purchase this costume from?

This item was sourced directly from the community. [Yes or No] - Frequency: How often do you engage with the community from which this culture comes?

I consume or celebrate aspects of this culture more than once a year. [Yes or No]

I advocate year-round for the causes that affect this community. [Yes or No] - Impact: Who might this harm?

I have considered who might be affected or othered by wearing this costume. [Yes or No]

I have made my best effort not to misrepresent this culture. [Yes or No]

I haven’t changed any core elements of the costume so that it remains true to the original culture. [Yes or No]

This costume does not require additional context to not be viewed as culturally appropriative. [Yes or No] - Consent: I have permission to wear this as a costume. (This is a tricky question because communities are not a monolith. No one person can permit cultural objects. However, being a part of the community makes one more likely to have insight into whether this is something to be shared with outsiders.)

If you answered no to any of these questions, this is a sign to find another costume.

There is unfortunately no straightforward answer to your questions, Hesitant Samurai, without first engaging in self-reflection. As we’ve highlighted, there are many things to consider before dressing up as Yasuke. By being a member of the executive leadership team, you hold significant power and privilege within your organization. To make your costume choice more inclusive, you most likely would have to explain the Yasuke origin story and what it means to you as a Black man. Due to your status within the organization, team members may not feel comfortable asking you to explain your costume, especially those with less power. So that you can wear this costume and feel confident that you’re not engaging in cultural appropriation, you need to ensure that you have cultivated a space where folks from all levels of the organization feel safe to engage in dialogue and ask questions without fear of retribution. The reality is that folks in executive-level positions will always hold more power, making it more challenging for people to really understand the nuances of your costume.

My suggestion? Find an alternative costume — one that doesn’t require ongoing explanation and one that better matches your organization’s DEI efforts. You can always go with The Black Panther. Chadwick Boseman was one hell of a hero on and off the screen.

To help you prepare for the festivities coming up on the 31st, here is a non-exhaustive list of non-inclusive Halloween costumes to stay away from:

- Day of the Dead/Sugar Skull makeup

- Aladdin

- Caitlin Jenner

- Drag Queen/King if you’re not actively involved in the community

- Anything done in Blackface/Brownface

- A Holocaust victim/survivor

- Sumo suit, body shaming suits

- Moana

- Pocahontas

- A terrorist

- Someone with an eating disorder

- Someone who is mentally ill (ie. wearing a straight jacket)

- Someone with a substance abuse issue

- Domestic violence couple (eg. Ray Rice, Whitney and Bobby)

- An unhoused person

- A sex worker

- The Black Lives Matter moment

- For white folks or white-presenting folks: any character in which their likeness is directly tied to their race/phenotype; ie. Foxy Cleopatra, Aladdin, Mulan, The Obamas, etc.

Not sure why a certain costume is on this list? We have you covered. On October 24th, we’re hosting a 1-hour session titled Celebrating Inclusively: Deconstructing Appropriation. Learn more and register here.